At the time of his death in New London in 1945, Frank Taylor Cable was recognized as the world’s foremost submarine engineer. He earned that reputation working with John Philip Holland, the visionary father of the modern submarine. When Holland’s prototype submarine sank to the bottom of Newark Bay after a careless crew member left open a valve, Holland’s dream almost sank with it. Frank Cable was a Connecticut native and young electrical engineer fresh out of Philadelphia’s Drexel Institute. After the unsuccessful attempts of many others, Cable suggested a novel idea to repair the submarine’s compromised electrical system. The success of that idea rekindled Holland’s dream and launched Frank Cable’s career. Cable’s technical talent and business instincts would eventually bring him to the pinnacle of New London society.

Frank Cable’s father, Abijah Cable, was born in New Milford, Connecticut. Abijah Cable was the great, great, great-grandson of John Cable, who emigrated from England to the new world in 1630. John Cable was among the early settlers of Roxbury, Massachusetts. In May of 1636, John Cable was also among a group of seven adventurers who left Roxbury to join William Pynchon in the settlement of Springfield, Massachusetts. Even before that date, John Cable and John Woodcock had scouted the area for Pynchon and built a crude house in the Agawam meadow in anticipation of the larger group’s arrival. William Pynchon was eager to expand the reach and influence of the Springfield settlement. In April of 1641, John Cable and Jehu Burr (believed to be Cable’s brother-in-law) sold their houses and lands to Pynchon, and relocated to Fairfield, Connecticut to become the area’s earliest settlers. Five subsequent generations of the Cable family remained in southern Fairfield County until the birth of Abijah Cable in 1826. Abijah Cable had two children with his first wife Paulina Jones, Frank Turney Cable and Charlotte P. Cable. Paulina Jones and her son Frank Turney Cable died within a day of each other in 1859. Abijah Cable was left by himself to raise his one-year-old daughter Charlotte. Soon thereafter, he met and married Olivia Taylor, daughter of Epapordituss and Rachel Taylor of Pine Plains, Duchess County, New York. Their only child, Frank Taylor Cable was born in New Milford, Connecticut on June 19, 1863.

Frank Cable attended Claverack College, a coeducational preparatory school in Hudson, New York. After just one year at Claverack, he returned home to work on the family farm due to his father’s advancing age. He remained at home until the age of twenty-five, after which he was hired in 1888 to work as a mechanic by the Gas Engine & Power Company of Morris Heights, Bronx, New York. Cable appears to have had no formal mechanical or engineering training prior to accepting this position. His mechanical skills were either self-taught or acquired on the job. Despite his lack of formal training, in 1890 Cable was hired as an electrical engineer by the Electro-Dynamic Company of Philadelphia. Electro-Dynamic Company manufactured electric motors and generators.

The management of the Electro-Dynamic Company quickly recognized Frank Cable’s talent and invested in his technical education. He first attended the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, where he studied mechanics, drafting, and engineering. Later, following the 1891 founding of the Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry (now known as Drexel University), Cable became one of its earliest attendees. Cable married Nettie Alice Hungerford of Sherman, Connecticut in Philadelphia on May 29, 1892.

It was during Frank Cable’s time with the Electro-Dynamic Company that he was first introduced to submarine pioneer John Philip Holland. Holland was born in Ireland, the son of an Irish Coast Guardsman. He developed conceptual drawings for a submarine while still in Ireland and further advanced the design following his 1873 immigration to the United States. Holland accepted a position as a lay instructor at St. Johns Parochial School in Paterson, New Jersey, and continued to work on his design when he could find the time. Holland’s drawings were eventually acquired by the United States Navy, under uncertain circumstances. They were reprinted in several Navy publications in 1875. Holland received no compensation but a measure of notoriety as a result.

The designs caught the attention of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood (IRB), the militant American chapter of the Fenian Brotherhood. The Fenians had launched several unsuccessful raids into Canada in the decade following the end of the American Civil War. Their goal was to gain control of portions of Canada to be used as leverage in Ireland’s struggle for independence from Britain. Although Holland’s younger brother Michael was a registered member of the IRB, there is no evidence that Holland himself was a Fenian. The IRB maintained a ”Skirmishing Fund” to finance its militaristic exploits, and John Holland was offered funding to produce a prototype of his design by the Fenians. The funding enabled Holland to bring his plans to life and resulted in the launch of the Holland I in Paterson on May 22, 1878. After several refinements, the Holland I demonstrated sufficient promise to convince the Fenians to finance the next generation submarine.

Work began on the Holland II, or the Fenian Ram (as it became known for its hoped-for ability wreak havoc on British ships) on May 3, 1879. The Fenian Ram was thirty-one feet long and six feet wide. It was powered by a Brayton gas engine and operated by a three-man crew. After a series of successful in-water trials and refinements, work began on the Holland III. The Holland III was a scaled down model of the Fenian Ram, that retained its basic elements but incorporated many improvements. Somewhat predictably, dissention within the ranks of the IRB stalled further development. In November of 1883, members of one of the Fenian factions stole the Fenian Ram and Holland III and attempted to tow them to New Haven. The Holland III broke free and sank in 110 feet of water off Whitestone Point. The Fenian Ram made it to New Haven Harbor but none of the absconders knew how to operate the vessel. The Fenian Ram remained, almost forgotten, in a lumber shed on the Mill River for over twenty years. In 1916, the Fenian Ram was exhibited in Madison Square Garden to raise funds for victims of the Easter Rising. She was then moved to the New York State Marine School. Thereafter, in 1928, she was purchased by Edward Brown of Paterson, New Jersey, and placed in Paterson’s West Side Park. Finally, in 1980, the Fenian Ram was moved inside the Paterson Museum where it serves as a memorial to John Philip Holland, the “father of the modern submarine.”

Following the tempestuous end to the Fenian Ram escapade, John Holland’s efforts to develop the world’s first modern submarine were more subdued, although he never lost faith in the project. His vision and designs had the support of a small, but committed cadre of naval officers, who internally pushed for the further development of the submarine. Holland’s enthusiasm was re-ignited in 1888 when the United States Navy announced an open competition for the design of a submarine torpedo boat. Despite repeated delays, in early 1893, congress finally appropriated $200,000 to fund the most promising entrant in the competition. Holland formed the John P. Holland Torpedo Boat Company in the spring of 1893 with sufficient financial backing to support his entry. After years of bureaucratic delay, Holland’s entry was declared the winner in September 1893, yet due to further internal wrangling within the Navy, a government contract to build the new submarine was not signed until March of 1895.

The boat to be built under the new Navy contract was known as the Plunger. It was a monstrously large vessel, primarily due to the Navy’s insistence that it be powered by a steam engine for operation above water. The boiler for such an engine occupied far more space than practical. Holland quickly became disillusioned by the constant oversight of Navy officers insisting on the inclusion of what he considered to be senseless modifications to his plans. As his dissatisfaction with the progress of the Plunger grew, Holland convinced the financial backers of the Holland Torpedo Boat Company to finance the simultaneous construction of Holland’s sixth submarine. This project would be a private venture, unhampered by the red tape, interference, and delay that saddled the Plunger project. The submarine was dubbed the Holland VI.

Frank Cable’s association with John Holland began with the production of the Holland VI. The new submarine was built at Nixon’s Cresent Shipyard in Elizabeth, New Jersey. The Holland Torpedo Boat Company claimed its intention was to develop the Holland VI in secrecy. Yet in John Holland’s words, the submarine was, “built to be placed on the market, and whoever has the price may buy it,” so there was a certain benefit to a more public development program. The company did not shy away from the frequent press inquiries and stories. An early account of the Holland VI project appeared in the March 17, 1897, issue of the Boston Herald, with a series of headlines trumpeting, “Fiction Outdone, Jules Verne’s Dream About to be Realized, Holland Submarine Monster Is Launched.” In the ensuing weeks, similar articles were printed in newspapers across the world. The very public nature of the Holland VI’s development made the United States Navy uneasy, especially with rising hostilities between Spain and the United States. Newspaper accounts reported rumors of strong interest in the Holland VI from Spain, Cuba, and France.

The public nature of Holland VI’s development also led to a collective public gasp when the project suffered its first major setback. On October 13, 1897, a careless workman accidentally left open a small valve on the boat. Water infiltrated the vessel throughout the night and by morning she had sunk to the bottom of the bay. After being pumped out and raised, it was clear to Holland and his team that the bay’s salt water had corroded the entire electrical system. The electrical generators (called dynamos) and all associated wiring were dead. If not repaired, the Holland VI would have to be dismantled so that each electrical component could be replaced. This course of action would set the project back months if not years. Several attempts were made by Chief Engineer Charles Morris, and others, to repair the damage to the electrical components over the next month. Most involved trying to apply external heat to dry out the components. All were unsuccessful. The company contacted the Electro-Dynamic Company of Philadelphia, the maker of the dynamos, to see if they had any suggestions as to the repairs. The Electro-Dynamic Company sent its promising young electrical engineer, Frank Cable, to study the problem. After examining the damage, Cable suggested that “there was only one way of remedying the trouble, and if this course was adopted, there was a chance of restoring the boat.” Cable ingeniously reversed the current in the armatures, which were the coiled wires of the dynamo, to generate internal heat. Within a week, the dynamos were ready for service. The batteries had been damaged, but Cable was able to recondition them by removing battery acid from the ship’s bilges and replacing all dead battery cells. Cable’s success was recognized immediately by all, and from that point forward, Cable became John Holland’s most trusted technician. Perhaps it was prophetic that as a token of the company’s appreciation for Cable’s invaluable service, it presented Cable with a captain’s hat. For within a few short months, Cable would be named the Captain of the Holland VI.

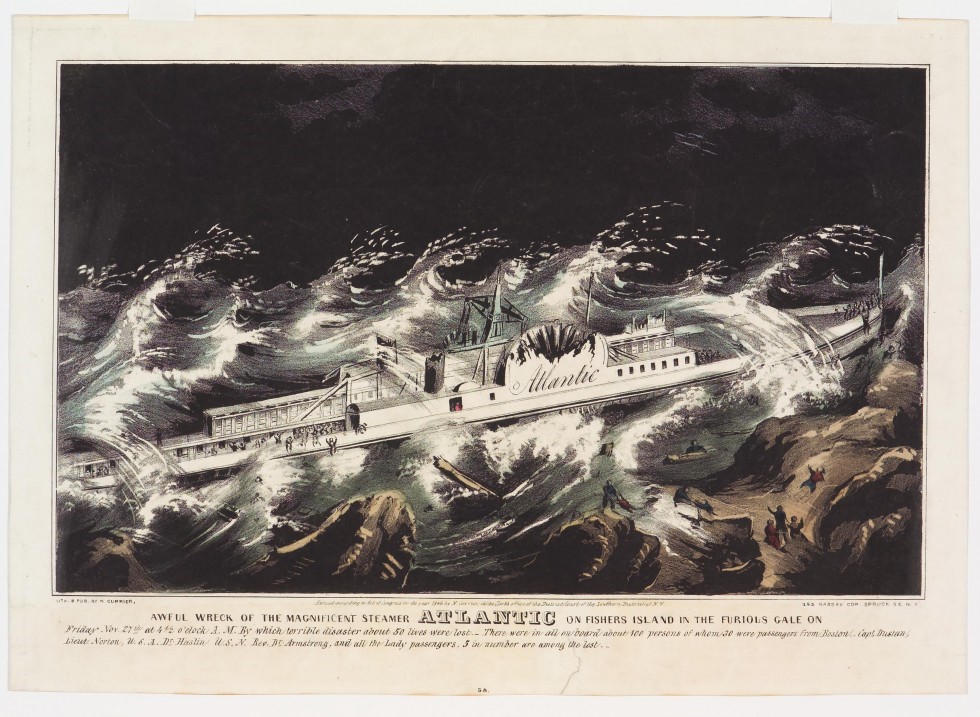

With the repairs to the electrical system completed, the ambitious testing and perfecting of the Holland VI resumed. Most of these trials were carried out with the eyes of curious reporters and a cautious Navy upon them. During one of these trial runs, the crew members of the Holland VI, quite unwittingly, found themselves in the middle of a scene of international intrigue. On February 7, 1898, the imposing Spanish warship Vizcaya left the Canary Islands to embark on a goodwill mission to New York City. While the Vizcaya was engaged in its crossing, the USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor, killing 266 crew members and naval officers. Though the cause of the explosion could not be immediately determined, lawmakers and the public instantly blamed Spain. The American Press, led by the “yellow journalism” publications of William Randolf Hearst, immediately decried “Spanish Treachery!” The incident brought to a climax the pre-war tension between the United States and Spain. The crew aboard the Vizcaya did not learn of the Maine disaster until it anchored off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, awaiting its escort into New York Harbor. The Vizcaya’s colors were immediately lowered to half-staff as a show of respect to the lost crew members of the Maine. The Vizcaya entered New York Harbor on February 20, 1898.

The Maine incident and the outrage it caused dramatically changed the public perception of the purpose of the Vizcaya’s visit. Newspapers published articles emphasizing the vulnerability of the city should the Vizcaya open up her guns upon it. The articles included dramatic graphics depicting shells landing upon city landmarks. There were fears in Washington that outraged individuals would view the presence of the Vizcaya as an opportunity to perform some act of sabotage against her. The Navy and the New York City Police were put on high alert to protect the Vizcaya at all costs.

It was into this tense situation that the Holland VI inadvertently strayed as she “cavorted around in the water near Staten Island, sinking, rising, plunging down, and whirling around with the easy gracefulness of a porpoise.” Speculation reached a fever pitch when observers witnessed the crew loading torpedoes (wooden dummy torpedoes with no warheads, as it was later learned) onto the submarine. Perhaps Holland VI was on the scene on behalf of Cuban revolutionaries or enraged Americans to attack the Vizcaya? Patrol boats were assigned to track every move of the Holland VI but given that so much or her movement took place under water, they soon lost track of her. New York citizens, who were feeling vulnerable due to the alarmist newspaper reporting, reassured themselves that the Holland VI was on the scene to menace the Spanish ship. Spanish and United States authorities could not rule out that possibility. In the end, after a peaceful mission, including formal expressions of condolence by the Captain of the Vizcaya and the Spanish Consul General to New York Mayor Van Wyck and United States Naval authorities, for the losses suffered by the crew of the Maine, the Vizcaya quietly left New York Harbor on February 25, 1898. The Boston Globe published an extra edition that same day bearing the headlines: “Vizcaya Sails, New York City Can Now Breathe Easy, SUBMARINE BOAT HOLLAND SCARED HER AWAY, Latter Had Cavorted About Staten Island.”

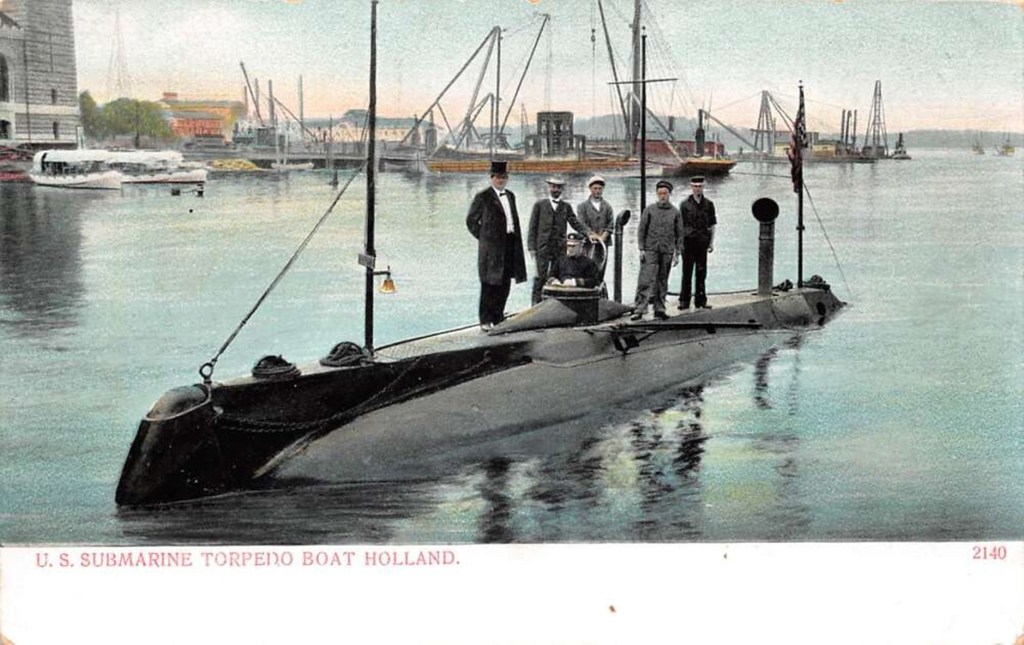

Following Frank Cable’s ingenious repair of the Holland VI’s electrical system, Holland moved quickly to make him a permanent member of the development team. Cable’s employer, the Electro-Dynamic Company of Philadelphia made the electric motor for the Holland VI. New York financier, Isaac Rice, had taken a controlling ownership interest in the Electro-Dynamic Company in 1892. Also, in 1897, Isaac Rice became the principal investor in, and was named President of, the Electric Storage Battery Company, which made the Holland VI’s batteries. With so many of his products in use on the submarine, Rice was keenly interested in its success, and he wholeheartedly supported placing Frank Cable on the Holland VI’s development team. Cable made his first dive aboard the Holland VI on March 27, 1898, the first in a series of scheduled demonstrations designed to convince United States Navy observers of the Holland VI’s capabilities. In June of 1898, Cable was named captain.

In the summer of 1898, Isaac Rice accepted an offer to take a test dive aboard the Holland VI. Rice’s enthusiasm for the project was obvious, and he did not hesitate to invest in the project when the Holland Torpedo Boat Company found itself in need of additional capital to further develop the Holland VI. Rice formed the Electric Boat Company in 1899, and then set up the Holland Torpedo Boat Company and the Electro-Dynamic Company as subsidiaries. In addition to Rice, the incorporators of Electric Boat included lawyer Elihu B. Frost, John Holland, and engineers Frank Cable and Lawrence Y. Spear. The base of testing operations of the company was moved to the Goldsmith and Tuthill Yard in New Suffolk, Long Island, on Little Peconic Bay, a quieter and more conducive location for extensive in-water testing.

The naval demonstrations continued over the next year and a half, all with Frank Cable in command. Cable proposed modifications, including the repositioning of the propeller to provide better stability when submerged, and the addition of additional ballast tanks. These were successfully incorporated into the submarine. On November 6, 1899, a demonstration of the Holland VI was conducted in Peconic Bay for the Naval Board of Inspection and Survey. This demonstration paved the way for a trip to Washington and a viewing by Admiral George Dewey. Dewey was the highest-ranking officer in the history of the United States Navy. Frank Cable piloted the Holland VI on its passage to Washington along the inland waterway, including passage down the Raritan River, through the Delaware and Raritan Canal, down the Delaware River, the Chesapeake Canal, the Chesapeake Bay, and after a brief stop at Annapolis, the Potomac River. Crowds numbering as many as five thousand people gathered at each town the submarine passed along the route and enthusiastically greeted Captain Cable and his crew.

The viewing by Admiral Dewey and several influential members of Congress proved to be an unqualified success. Hearings before the House Naval Committee followed the demonstrations on the Potomac. Despite that many naval officers and congressmen were skeptical about submarines in general, particularly due to the money that had been expended, and wasted, on the Plunger, the United States Navy purchased the Holland VI on April 18, 1900. The Navy assigned the submarine to Narragansett Bay, and Frank Cable was engaged to train her first Navy crew.

The Navy soon contracted with the Holland Torpedo Boat Company for six additional submarines based on the Holland VI’s design, but with significant improvements. These would become known as the Adder Class of submarines. The Holland Torpedo Boat Company determined that it should build a prototype of the Adder Class submarine at its own expense, to test the improved design. This submarine was known as the Fulton. Frank Cable was in command of the Fulton throughout its trials in Peconic Bay. As with the Holland VI, the general public took a keen interest in these sea trials. Foreign governments had now also become interested in submarine technology. They frequently sent representatives to observe, and when invited, participate, in the sea trials. In November 1901, Frank Cable, with his own crew and two United States Naval officers, remained submerged for fifteen hours. This demonstration silenced skepticism about the length of time a submarine could safely remain under water. A violent gale passed overhead as the Fulton lay on the sandy bottom, but conditions aboard remained so unaffected that the crew did not learn of the storm until they re-surfaced the following day. Newspapers throughout the country carried the news with the New York Tribune declaring, “Submarine Boat Surpasses Fondest Dreams.”

With the success of the trials on Long Island, the Fulton was summoned to Washington, just as the Holland VI had been, to conduct demonstrations there. On route, while taking refuge from a storm within the Lewes Delaware Breakwater, an explosion caused by the ignition of battery gas rocked the Fulton as the crew was preparing breakfast on an electric stove. Luckily, there were no deaths caused by the explosion, but three men below deck were injured, including one who lost a significant portion of his scalp and another who was struck in the head by the flying coffee pot. Again, the newspapers across the nation eagerly reported the setback. The Fulton was rendered out of commission, and the Washington trials were completed by the Adder, the first of the six new submarines built for the Navy, which was by then in a forward state of completion. The five Adder Class submarines were, like the Holland VI, built at Nixon’s Cresent Shipyard in Elizabeth, New Jersey. They were delivered to the US Navy in 1903.

As foreign governments began purchasing Holland-built submarines, Frank Cable spent the next several years traveling to these nations to train the crews that would operate them. In 1901, the British government purchased the rights to build five Holland Class submarines, and Cable was sent with a team of Americans to train the crews. The Fulton was reconditioned and sold to the Russian government in 1904, in the midst of the Russo-Japanese war (1904-1905). The Holland Torpedo Boat Company was unsure of how the United States government would view the sale of a submarine to a nation in the midst of a war in which the United States maintained its neutrality, so the transfer of the Fulton out of US waters took place in a clandestine manner. The submarine was renamed the Madam upon arrival in Russian waters. Cable and a small crew travelled to Russia to supervise its offloading and reassembly, train a Russian crew, and conduct sea trials. Frank Cable met Tsar Nicholaz II as the Madam was being prepared for transport by rail from Petrograd to Vladivostok.

In early 1905, the Holland Torpedo Boat Company, landed a contract to sell five Adder Class submarines to Japan. With this order, the Electric Boat Company had outgrown the capacity of Nixon’s Shipyard in New Jersey. The boats were built and assembled, under a subcontracting agreement, with the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts. They were then partially disassembled for shipment and reassembled in Japan. Once again, Frank Cable was assigned the task of going abroad to supervise the reassembly of the submarines, conduct trials, and train Japanese crews to operate them. The crossing of the Pacific to Yokohama in wartime, with a large supply of war materials on board the steamer on which he travelled, caused Cable great concern that the journey would be disrupted by the Russian fleet. Upon safe arrival, Cable was impressed by the efficiency with which the Japanese Navy reassembled the submarines and conducted the sea trials. Just as the first submarine was formally accepted by the Japanese Navy and loaded with torpedoes for its first mission, peace was declared in the Russo-Japanese war. Cable recalls the men he trained as being deeply disappointed.

The next class of Holland type submarines developed was the C Class, the first of which was named the Octopus. These were also constructed in the Fore River Shipyard. Frank Cable again led the testing crew. The testing protocols announced by the Navy included a requirement that the Octopus should remain totally submerged for twenty-four hours, without communication from the shore. Cable and his crew accomplished the feat, without incident, in Narragansett Bay on May 15-16, 1908.

As the evolution of Holland submarine boats continued, the Navy required the transition to the use of diesel engines to eliminate the risks associated with the use of gasoline. The Electric Boat Company had obtained the patent rights to the German MAN diesel engine and began manufacturing them in the United States. At first, they were produced at the Fore River Shipyard. Frank Cable was assigned the task of locating a permanent site for the manufacturing of diesel marine engines. The selection by Cable of a site on the Thames River in Groton, Connecticut ultimately resulted in Groton becoming the permanent home of the American submarine industry. By 1910, Electric Boat incorporated a subsidiary named New London Ship and Engine Company (NELSECO) to manufacture the MAN-based diesel marine engines. Isaac Rice led the Board of Directors and Frank Cable was selected to serve as the company’s vice-president and general manager. Construction on the modern NELSECO plant began immediately after its organization and the New London Day reported that its equipment was being installed by March of 1911. Cable was appointed general manager of Electric Boat following a 1930 reorganization of the companies, and served as a consulting engineer in his later years.

At the time of the 1900 United States Census, Frank Cable’s wife, Nettie Hungerford Cable, was living as a boarder with her sister May Hungerford Wheeler and her husband William P. Wheeler at their home at 140 Bradley Street in New Haven, Connecticut. Frank Cable is not listed as a resident of the same household. At that time, Cable was either in Washington D.C. conducting sea trials on the new Adder Class submarines, supervising their construction at the Nixon Shipyard in Newark, testing them in Long Island’s Peconic Bay, or training a Navy crew to operate the recently purchased Holland VI at the Naval Torpedo Station in Newport. On June 24, 1904 the Newton Bee reported that Frank and Nettie Cable were in her hometown of Sherman, Connecticut. They were there visiting the home of Frank Cable’s half-sister, Charlotte Cable Hungerford, who had married Nettie Cable’s cousin, Mills Hungerford. The article notes that they made the trip in Frank Cable’s automobile, which indicates Cable was an early embracer of yet another technology. Frank and Nettie must have spent a great deal of time separated from one another, although a September 15, 1905 article in the New Haven Journal-Courier reported that Nettie Cable was with her husband on his trip that year to Japan and that she had been with him on the prior year’s trip to Russia.

At the time of the 1910 United States Census, Frank and Nettie Cable were living at 9 Grand View Avenue in Quincy, Massachusetts. This home was just a short distance from the Fore River Shipyard. Living with the couple at the time was Frank Cable’s mother Olive Cable, Nettie Cable’s aunt Mary Hungerford, Nettie Cable’s younger sister Eva Hungerford, and a live-in domestic servant from Sweeden named Emma Gustafson.

Frank and Nettie Cable moved from their home in Quincy, Massachusetts into the Mohegan Hotel on State Street in New London in April of 1911. That same month, Cable leased the Giles Bishop house at 606 Montauk Avenue, and after some renovations, he and Nettie moved into the home in June. Frank Cable’s mother Olivia Taylor Cable continued to live with Frank and Nettie Cable until her death in 1928 at the age of ninety-three. To commute from his new home in New London, Frank Cable operated a private launch from T. A. Scott’s wharf at the foot of Thames Street to the NELESCO plant in Groton.

Frank and Nettie Cable became prominent members of New London Society. Frank Cable became a member of the Board of Directors of the New London Building and Loan Association and later served as that institution’s president. He was a frequent speaker at meetings of local civic and professional organizations. Nettie Cable directed the Red Cross “wool department” making and collecting knitted items for those impacted by the first world war. She was active in the Women’s League of the Second Congregational Church, and raised funds for the Home Memorial Hospital. One of the biggest social events of 1916 took place when Frank and Nettie Cable hosted the wedding of her sister Eva Hungerford to T. A. Scott employee Stephen Gardner at their home on Montauk Avenue. The Day reported that Frank and Nettie Cable celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary at their home on May 29, 1942.

At the outbreak of the first world war, the United States counted thirty submarines among its fleet. During World War I, eighty-five Electric Boat submarines powered by NELESCO diesel engines and Electro-Dynamic Company electric motors were manufactured for the United States and its allies. Frank Cable expertly managed this rapid increase in production and expansion of facilities. Contracts for NELSECO diesel engines fell dramatically following the war, and Frank Cable was now forced to manage a business in decline. The December 8, 1920, Norwich Bulletin reported that the New London Ship and Engine Company, which had employed more than 1000 skilled mechanics and draftsmen during the war, was then employing 650 people, and had been laying off 50 employees per week, a pace it planned to continue unless new contracts could be secured. The Bulletin also reported the company announced wage reductions of between ten and twenty percent on February 16, 1921. The New London Day reported that NELSECO laid off 300 employees in July of 1924 due to the lack of contracts and slow payment by the United States of lingering WWI era debt. The efficient management of the local workforce levels to meet pending and future contract obligations was a recurring theme during Frank Cable’s tenure at NELSECO and Electric Boat, just as it is today.

Frank T. Cable died on May 21, 1945 at Lawrence Memorial Hospital in New London at the age of eighty-one. His wife Nettie was his sole survivor. He had been a resident of New London for thirty-four years. He was buried in his hometown of New Milford, Connecticut.

Researched, written, and edited by the students of the course entitled, “New London Stories,” Christopher Kervick, Instructor, Mitchell College, Thames at Mitchell Program, Fall Semester 2024. William Federowicz, Jillian Grossbach. Olivia Herek, Shawn Kaye, Jacob Lincoln, Anni Lockwood, Juliona Lynne, Patrick McGuinness, Taylor Peck, Jack Pilotte, Noah Rase, Maggie Rotelli, Joseph Ruggiero, Grace Schiermbock, Madeleine Shuster, Tyler Solomon, Raphael Weiss.

Bibliography

1. Archives of The New London Day, The Hartford Courant, The Norwich Bulletin, The Journal (Meriden), The Morning Jopurnal (New Haven), The Newtown Bee, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Boston Evening Transcript, The Boston Globe, The Chicago Tribune, The New Britain Herald, The New York Herald, The Baltimore Evening Sun, The Philadelphia Times,

2. United States Census: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940, 1950.

3. New London Land Records

4. New London City Directories.

5. Hale Index, Connecticut Cemetery Inscriptions.

6. Morris, Richard Knowles, John P. Holland, 1841-1914, Inventor of the Modern Submarine (University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC, 1966,1998).

7. Cable, Frank Taylor, The Birth and Development of the American Submarine (Harper & Brothers, New York, 1924).

8. Ancestry.com.

9. Findagrave.com.

Leave a reply to John Morgan Cancel reply