Researched, written, and edited by the students of the course entitled, “New London Stories,” Christopher Kervick, Instructor, Mitchell College, Thames at Mitchell Program, Fall Semester 2025. Maggie Craco, Vincenzo Dilorenzo, Fabrizio Fiondella. William Lombardo, Danielle Luongo, Billy Mirabella, Sam Mongeon, Emily Rosen, Brendan Winters, Micaella Young.

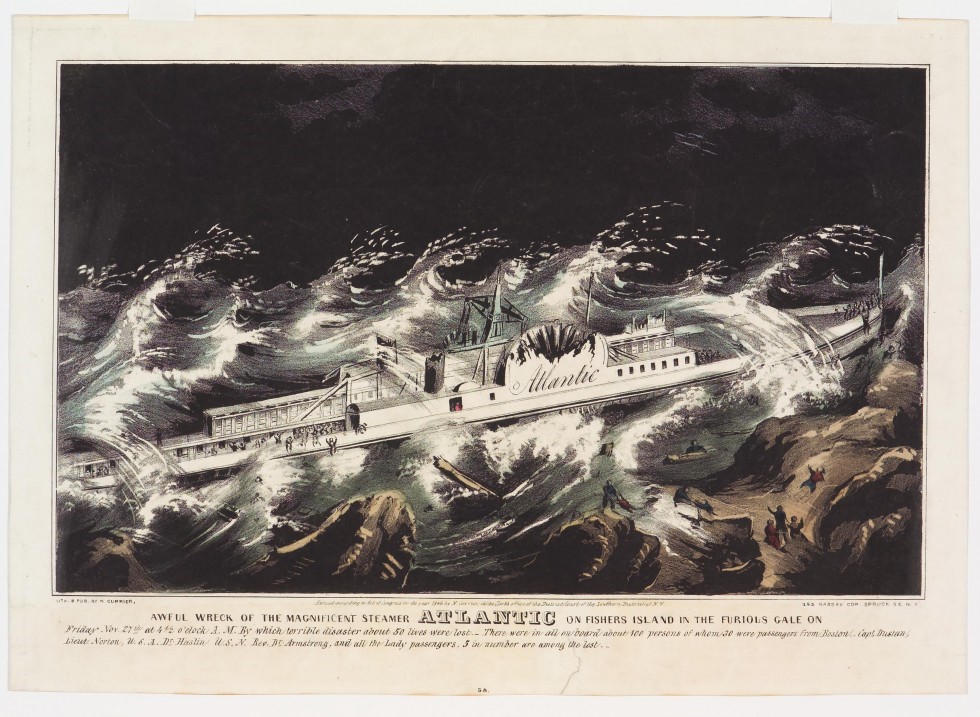

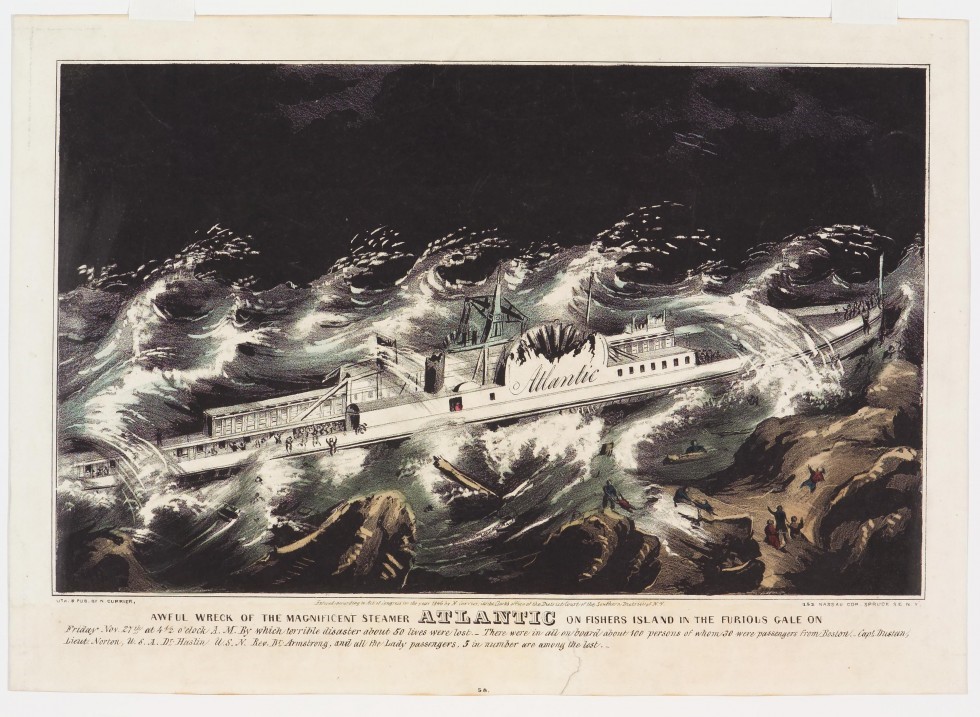

Tragedy can either destroy a person or motivate them. On Thanksgiving Day, 1846, a violent early winter storm transformed the usually calm waters of Fishers Island Sound into a sea of sorrow. The Atlantic, the pride of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s steamboat fleet, was reduced to splinters as it was dashed upon the rocks of Fishers Island. Fifteen-year-old Jacob Walton miraculously survived the wreck, but the six remaining members of his family were among the forty-two souls who perished. Every person Jacob loved was lost. As the Waltons had recently immigrated from England, Jacob had no local family to rely on for emotional support.

The New London community showed great kindness toward the Walton family and Jacob. Citizens pooled their resources to fund a proper burial and monument, put aside sectarian differences to arrange a community-wide funeral service, and joined the lengthy funeral procession to New London’s Third Burial Ground to mourn alongside the distraught youngster.

Jacob’s grief understandably overwhelmed him. His world had been turned upside down in an instant, and he faced an uncertain future. He could have let the loss destroy him, but over the ensuing years and throughout the remainder of his life, he exhibited tremendous resilience. The tragedy instilled in Jacob Walton a steel-like determination to succeed, and he used that motivation to build a legacy that has now spanned nearly two centuries.

Jacob Walton was born in Middleton-on-Teesdale, County Durham, England on February 6, 1831. He was the second child born to John Walton and Jane Addison Walton. John and Jane were married on September 26, 1824. John was a miner at the time of his marriage and when his first child, Mary Ann, was born in 1827. By the time of Jacob’s 1831 birth, John had entered the masonry trade. The couple had three more children, John in 1833, Eleanor in 1835, and James in 1841. The family briefly lived in the nearby town of Bernard Castle, but by the time of John, Jr.’s birth they had moved to Bishop Auckland. All three towns were within a short distance of each other.

At the time of the 1841 census of England, the Walton family was living in Bishop Auckland, sharing a home with Jane’s mother, Mary Addison. Also living in the same home, were Jane’s brothers, James and John Addison. James Addison was also a mason and John was a mason’s apprentice. Living conditions must have been cramped, as three fifteen-year-old mason’s apprentices also shared the same home. The extension of the Bishop Auckland and Weardale Railroad, which began in 1837, created a growing local demand for trained masons. They were needed to construct the bridges, tunnels, arches and culverts associated with the extension project. This need may explain the high concentration of masons in the Walton/Addison household.

John Walton suffered a financial setback while living in Bishop Auckland. Both the March 5, 1841 edition of the Newcastle Courant and the March 6, 1841 edition of the Newcastle Journal reported the case of James Addison v. Sir Hedworth Williamson. Williamson was the High Sheriff of Durham at the time. Although John Walton was not a party to the action, his debts led to the litigation. A man named Iveson had previously successfully sued John Walton to recover monies owed to him. When Walton could not pay the judgment, a writ was issued by the High Sheriff to levy Walton’s assets. This was accomplished by entering their home and removing all of the furniture, which was subsequently sold to partially pay the debt. James Addison claimed that the furniture was not Walton’s, but his own, as the Walton family was only temporarily living in the home. Addison wanted the proceeds of the sale of the furniture returned to him by the High Sheriff. After a full trial, despite a great deal of evidence favoring Addison’s claim, the jury returned a verdict against him. Addison’s kindness in allowing his sister and her large family to move into his home cost him all his furniture. Shortly thereafter, to avoid further collection efforts, and perhaps to avoid the ire of his brother-in-law, John Walton and his family left England for the United States.

Jacob Walton’s application for citizenship notes that the Walton family arrived in the United States in June of 1842. The family temporarily settled in West Newbury, Massachusetts, which was at the time the hub of the comb-making industry in America. Jacob found work in the comb factory of Somersby C. Noyes, who was the grandson of industry pioneer, Enoch Noyes.

John Walton never planned for the family to permanently settle in West Newbury. They began saving to fund a relocation to Pennsylvania. Family oral history suggests that their plan was to purchase farmland in the Lancaster area.

While in West Newbury, Jacob’s older sister, seventeen-year-old Mary Ann Walton, fell in love with another recent English immigrant, Robert Vine. The family left West Newbury for Pennsylvania just two weeks after the young couple’s November 13,1846 marriage.

At the time of their journey, the most convenient route from Boston to New York included travel by train and steamship. After leaving Boston, the train made a stop in Worcester, and then proceeded to the dock at Allyn’s Point, which was on the Thames River just below Norwich. Passengers then transferred to a steamer bound for New York, making a brief stop in New London on the way. The trip generally lasted just ten hours. The same trip from Boston to New York was a six-day ordeal fifty years earlier. This route was sometimes called the “inland route” as it avoided traveling through Providence and the rougher waters of the Narragansett Bay, Atlantic Ocean and Block Island Sound. The convenience of the trip was further enhanced when the steamship Atlantic was placed into regular service on August 18, 1846.

The Atlantic was the most luxurious passenger steamer of its time. At three hundred and twenty feet in length, it was the largest steamer built in the United States. It had three decks, with separate men’s and lady’s cabins, and an elegant, 250-foot saloon on the upper deck. Its 1,373 horsepower steam engine provided the fastest travel available on the waters of Long Island Sound.

When the Walton family set out for Philadelphia on November 25, 1846, they boarded the Worcester & Norwich Line train at Worcester, then switched to a steamer at Allyn’s Point for the remainder of the trip to New York

An early winter storm had been brewing the entire day, and conditions worsened considerably as the steamer stopped in New London. It was nearing 11:00 pm and Captain Isaac K. Dunstan had not yet decided whether to make the trip. Ultimately, he made the fateful decision to proceed.

There are two heart-wrenching aspects of the loss of the Atlantic that stand out most. The first was the excruciatingly long period of time between the bursting of the steam pipe of its boiler, rendering the ship powerless, and when she finally wrecked upon the rocky shore of Fishers Island. The steam pipe burst at 2:00 am on Thursday, November 26th and for twenty-six hours she floundered in tempestuous seas, her anchors unable to hold her steady in the raging storm, until crashing at 4:00 am on Friday November 27th. Several rescue attempts were made but all were unsuccessful. There was no way for a rescue ship to approach the Atlantic without risking its own loss.

The second horrifying aspect of the loss of the Atlantic was the sheer violence of the crash upon the rocks of Fishers Island, and the mutilation of the passengers who were unable to distance themselves from the wreckage. All women and young children on board, as well as most elderly passengers, gathered in the lady’s cabin as the ship neared the shore of Fishers Island. Surviving passengers recalled that upon first impact, the entire cabin slid off the deck and shattered on the rocks. All those who sought shelter in the lady’s cabin were either killed instantly or crushed by the repeated pounding of the hull of the ship onto the remains of the cabin.

Survivors also reported seeing Jacob Walton, flailing in the turbulent water amid floating baggage and debris, struggling to get to shore.

During the remainder of the night, those who survived were brought to Winthrop’s farmhouse on Fishers Island, while islanders and a few able survivors pulled mangled bodies from the sea and rocky shore. The next morning, as the weather subsided, the steamer Mohegan arrived to transport the survivors and the twenty-two bodies recovered by that time, back to New London. Among the bodies initially brought in by the Mohegan were Mrs. Jane Addison Walton, Mrs. Mary Ann Walton Vine, John Walton, Jr., James Walton, and Eleanor Walton. The body of John Walton, the father, was not recovered until the following day. Jacob Walton, and his new brother-in-law, Robert Vine, survived. In all, forty-two passengers and crew members were lost. Sixty-four passengers and crew members survived.

Following the memorial service for Jacob’s family provided by the New London community, Jacob was alone in his grief. Aside from the pain of his loss, he also must have wondered about his long-term survival. His father’s body was recovered on the day of the funeral and buried beside his family the following day. In a pocket of John Walton’s coat was found $285 in banknotes and $10 in gold coins. Another $2,600 was found in the family’s recovered baggage. There were reported instances of local citizens rifling through the pockets and bags of passengers as they washed up on shore over the next several days, so the fact that these funds were preserved for Jacob’s benefit is a testament to the respect for Jacob and his family displayed by the citizens of New London. To this day, Jacob’s descendants fondly regard New Londoners for the kindness they showed. More importantly, the recovery of these funds provided Jacob with a modest means of support.

Both Jacob and Robert Vine, having no other practical options, returned to West Newbury, Massachusetts in the days following the funeral.

Robert Vine went into the comb-making business, joining an enterprise financed by local dry good merchant, Charles H. Coffin. On July 6, 1848, Robert Vine married Coffin’s daughter, Ann Maria Coffin, and the couple had eleven children together. Vine remained in West Newbury until his death on January 27, 1904.

Upon Jacob Walton’s return to West Newbury, he lived in the home of William Noyes. William was the grandson of Enoch Noyes. William Noyes was a brilliant inventor and machinist, although his comb-making family considered him to be a bit eccentric. Jacob worked in the machine shop of William Noyes, helping design and maintain machinery used in the comb-making industry. The following year, Jacob began a formal apprenticeship in the shop of Somersby C. Noyes, a company for which he had worked upon first arriving in West Newbury. Jacob used his modest nest-egg, recovered from the wreckage of the Atlantic, to fund his attendance for one year at the historic Gilmanton Academy in New Hampshire.

In 1852, Jacob’s mentor, William Noyes, left West Newbury to open a new machine shop in Newark, New Jersey. William’s brother, David Noyes, another comb-making pioneer, had left West Newbury in 1846 to establish a successful comb-making enterprise in Newark. Jacob joined William on his journey hoping to establish his own comb-making business. He was unable to obtain the machinery he needed to open his own shop, so he joined the firm of David Noyes as a journeyman.

In 1852, Jacob Walton married Elizabeth Wilcox of Roxborough, near Philadelphia. That same year, he moved to Philadelphia and entered into a partnership with Edward E. Warner, to establish his own comb-making enterprise. Business uncertainties caused by the outbreak of the Civil War led to a temporary dissolution of the partnership. During this time, Jacob Walton supported himself by manufacturing and distributing cigars.

Jacob had three children with Elizabeth Wilcox Walton, namely, John in 1856, William in 1858, and Mary in 1859. Mary Wilcox Walton died in 1862 and later that same year Jacob married her first cousin, Henrietta Ellis. Jacob and Henrietta had four children, Charles in 1864, Henrietta in 1866, Eleanor in 1870, and Samuel in 1873. Henrietta Ellis Walton died from complications related to Samuel’s birth on March 12, 1873 and Samuel died several days thereafter. Jacob then married Henrietta’s sister, Margaret “Maggie” Ellis, later in 1873. Jacob and Maggie had two children together, George in 1877 and Emma in 1879.

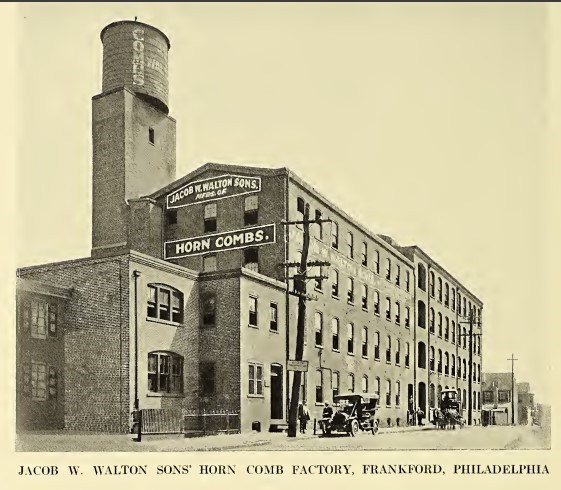

Jacob had reestablished his partnership with Edward Warner when the Civil War ended, and they opened a comb-making factory on Wheat Sheaf Lane in Philadelphia, which was successfully conducted until Warner’s retirement in 1875.

Following Warner’s retirement, Jabob Walton brought his sons John, William, and Charles into the business. The firm grew steadily, and the company built a large factory in the Frankford section of Philadelphia in 1892. Jacob Walton died the following year, on February 1, 1893. The business was then successfully operated well into the 1920s by Jacob’s sons and grandsons.

On September 2, 1909, The New London Day reported that Jacob’s son, John Walton, visited New London to learn all that he could about the deaths of his grandparents, aunts, and uncles on the Atlantic in 1846. The article notes that he visited Cedar Grove Cemetery and photographed the monument erected to the family’s memory. Just as they did in 1846, the citizens of New London exhibited a great deal of kindness toward the family and arranged for John Walton to meet with several citizens with detailed knowledge of the wreck.

The wreck of the Atlantic was a calamity that ended the lives of each of Jacob Walton’s family members, and although the loss was surely devastating, Jacob refused to let the tragedy defeat him. He placed the hopes and dreams of his entire family upon his young shoulders, and met that challenge with determination and grace.

Bibliography

1. Archives of The New London Day, The Newcastle Journal, The Newcastle Weekly Courant, The Yorkshire Herald, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Philadelphia Times, The Springfield Weekly Republican, The Brooklyn Eagle, The Brooklyn Evening Star, and The Atlantic City Gazette.

2. United States Census: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940, 1950.

3. Census of the Township of Bishop Auckland, 1841.

4. England, Births and Christenings,1538-1975, database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NT5W-KZC.

5. Middleton in Teesdale Baptisms 1753-1841.

6. Hale Index, Connecticut Cemetery Inscriptions.

7. Doyle, Bernard, Comb Making in America, An Account of the Origin and Development of the Industry. (Viscoloid Company, Leominster, MA, 1925).

8. Larsson, Eric, The Captain, The Missionary, and The Bell, (Covenant Books, Murrells Inlet, SC, 2020).

9. Rafferty, Pierce, Wreck of Steamer Atlantic, recorded illustrated talk, Henry L. Ferguson Museum, July 14, 2023.

10. Caulkins, Frances Manwaring, History of New London, (H. D. Utley, New London, 1895).

11. Ancestry.com.

12. Findagrave.com.

13. Personal interview with Timothy Ireland, great, great, grandson of Jacob Walton.